Hawthorne Municipal Airport’s roots lie in the early days of the aerospace industry

Posted on May 7, 2016 by Sam Gnerre

Original DailyBreeze article HERE

Hawthorne Municipal Airport’s control tower in 2013. (Daily Breeze staff file photo)

Hawthorne Municipal Airport, one of the busiest, most thriving general aviation airports in California, began as a dirt landing strip built by the city of Hawthorne in 1939. It was part of a deal the city made the year before to entice an aviation entrepreneur to build his factory there.

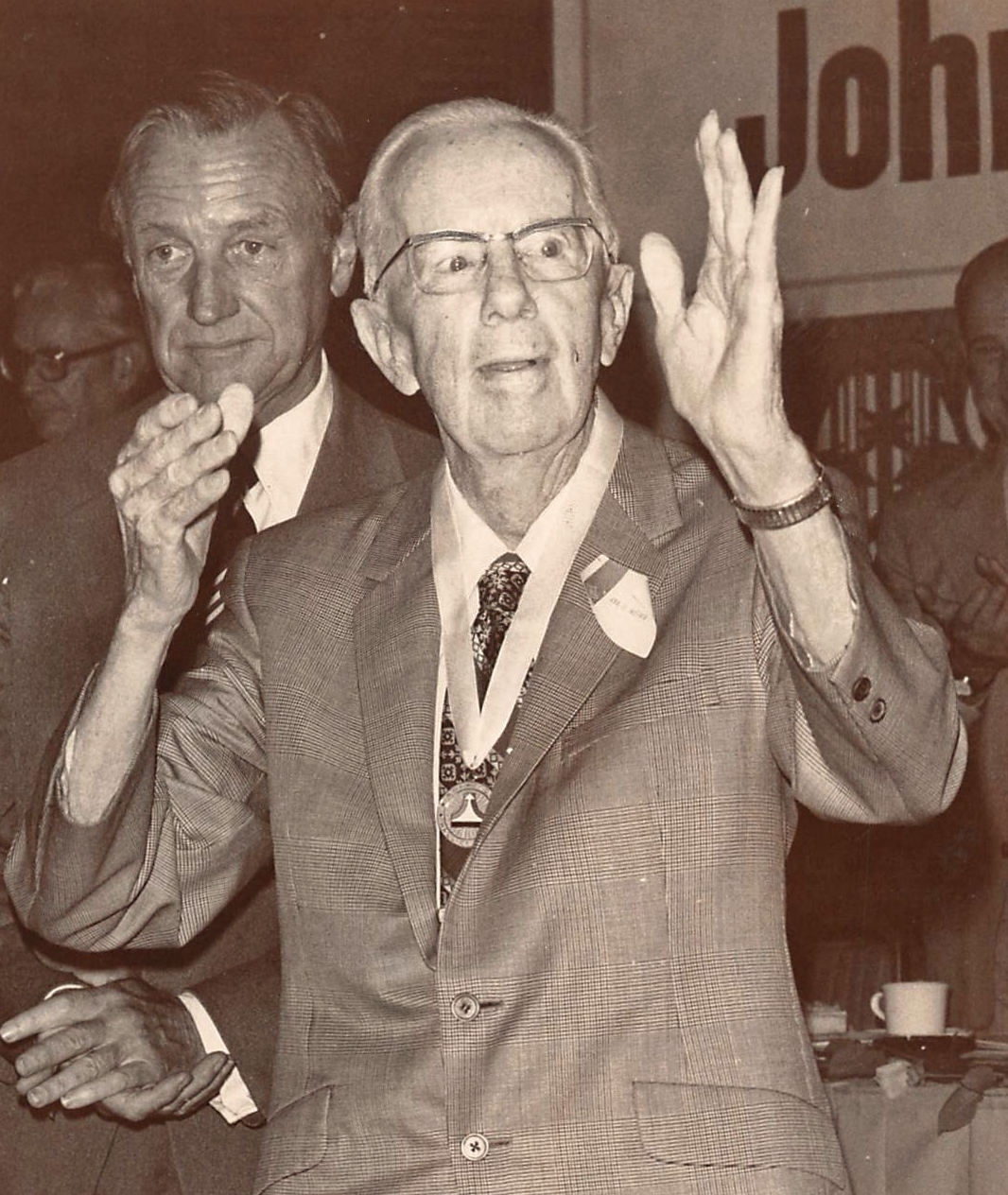

Jack Northrop acknowledges an ovation at a luncheon on Aug. 2, 1978. He died at 85 in 1981. (Daily Breeze staff file photo)

The one- mile long, 700-foot-wide landing strip, located between Prairie Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard just south of 120th Street, was built for aviation pioneer Jack Northrop, who had spent the summer of 1939 forming his new independent aviation manufacturing firm Northrop Aircraft, Inc. Its home was to be a 72-acre site leased with option to buy from the city, and the airstrip was christened Northrop Field.

Northrop had begun his career in aviation in 1916, working as an engineer for the Loughhead brothers in Santa Barbara. He joined with Allan Lockheed (who changed his name from Loughhead because it was easier to spell) and other partners in 1927 to form Lockheed Aircraft, where he developed the Lockheed Vega, a small, fast general aviation monoplane flown by the likes of Wiley Post, Amelia Earhart, and other early aviators.

He left Lockheed in 1928 to form the Avion Corporation, a small firm where he felt more free to develop his creative ideas, including the very first iteration of the Flying Wing, a concept he would return to throughout his career. We wrote about the Flying Wing in a 2011 post.

Boeing became interested in Northrop’s ideas and brought Avion into its corporate structure under the Northrop Aircraft Corporation name. When Boeing’s owners, United Aircraft, wanted to move Northrop’s firm to Kansas, he split off and formed another Northrop Corporation in conjunction with Douglas Aircraft of Santa Monica.

But he became restless again, splitting off from Douglas in 1938 to finally form a truly independent firm with the Northrop name.

Northrop met with a group of engineers and managers at the Hotel Hawthorne to form the new firm, designing a 122,000-square-foot factory for which they broke ground on Sept. 30, 1939.

Northop’s plant, right, still has wartime aerial camouflage in this 1946 aerial view looking east, with runway at left. (Photo from “Northrop: An Aeronautical History”)

The adjoining airstrip was crucial to Northrop’s plan, as he needed it in order to roll planes off the factory’s assembly line and fly them directly to Muroc in the Mojave Desert for testing. (The Muroc airfield would become Edwards Air Force Base in 1949.)

Northrop moved into its new Hawthorne home in February 1940. The company grew rapidly, from its original six to 109 employees in just a few months. Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, Northrop Field was taken over by the U.S. government’s War Assets Administration for use in the war effort.

The government returned Northrop Field to the city in November 1946, when it declared the 40 airports it had taken control of in Southern California and Arizona during the war as surplus property.

On April 24, 1948, Hawthorne Mayor Harold E. Crozier issued an official proclamation renaming Northrop Field as Hawthorne Municipal Airport, and opened it to private aircraft. Northrop deeded its share of the property to the city, and continued to use it under a lease-back agreement, a provision of which was that the land must continue to be used as an airport or title would revert to Northrop.

Northrop and the airport prospered under the arrangement during the 1950s, even though the airport’s tower only operated during daylight hours. For nighttime flights, air controllers at Los Angeles International Airport had to guide planes in and notify Hawthorne so it could turn on its runway lights.

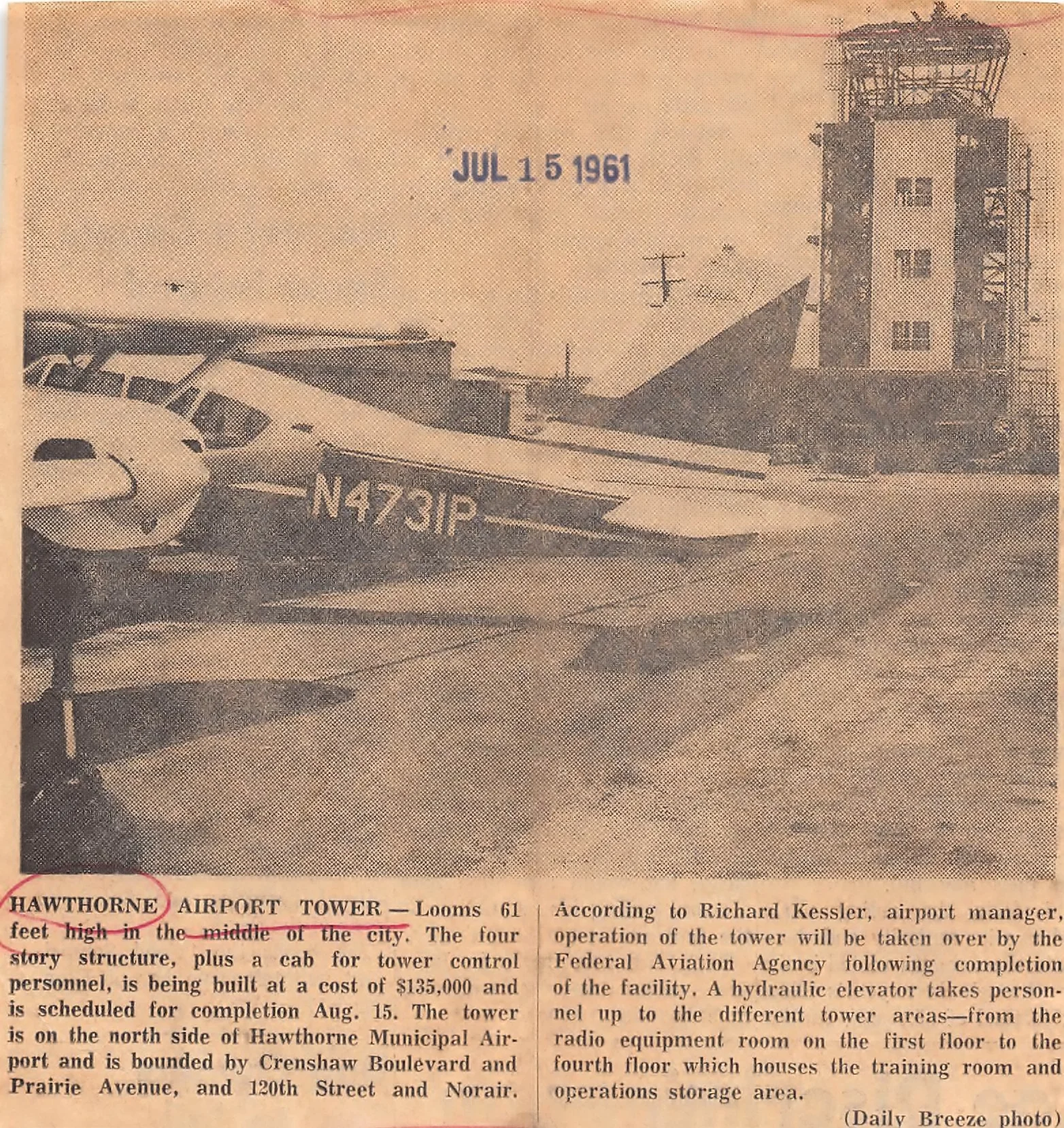

The new control tower under construction at Hawthorne Municipal Airport. Daily Breeze, July 15, 1961.

The city pushed to get approval for a new control tower that would be staffed by Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) personnel and be open from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. at the busy airport, which logged more than 143,000 flights in 1960. Ground was broken for the new $135,000 tower on April 15, 1961, and the 50-foot-tall structure was dedicated on Oct. 28, 1961.

Further development plans had been set in motion by the city, including the addition of more hangars and the construction of a two-story airport terminal building that would house a large restaurant as well as offices and an observation deck.

Glenn Anderson speaks at the dedication for the new terminal at Hawthorne Muncipal Airport on April 2, 1966. Daily Breeze, April 3, 1966.

It would take a few years to become a reality, but the new building was dedicated on April 2, 1966. California Lt. Gov. Glenn Anderson, who later served as the area’s congressman for decades, delivered the keynote address before 1,200 attendees. At the time, Hawthorne Municipal Airport was ranked as the 7th busiest such facility in California and the 23rd busiest in the nation.

Though aerospace and private business dominate its activities, the airport has its appeal to the general public. In 1983, airport director Robert Trimborn started the popular Hawthorne Air Faire, which was held there for the next 22 years.

The airport also was home to the Western Museum of Flight for 24 years, until that facility lost its lease in 2006. It reopened in 2007 in smaller quarters at the Torrance Municipal Airport.

The airport has had its detractors over the years. City Finance Director Sam Takata noted in 1984 that the airport cost about $450,000 a year to maintain and produced only $100,000 in revenue. As the city’s financial fortunes began to ebb, the airport started to be seen as a drain on its coffers.

In 1999, Pacific Retail Trust, a development firm, proposed leveling the 80-acre airport and turning it into a shopping center complex that would generate $3 million in profits instead of the $80-100,000 produced annually by the airport.

In June 2000, Arden Realty of Los Angeles proposed building a 70,000-seat pro football stadium with a hotel, theme park, museum and restaurants on the site, saying that it would generate $9.4 million annually in revenue.

The city decided to put the fate of Hawthorne Municipal Airport in the hands of voters in 2001. File photo, June 25, 2001. (Robert Casillas / Staff Photographer)

Another developer, Paladin Partners, began negotiations with the city that September to build its version of an entertainment and retail complex on the site.

Pilots and aviation buffs denounced all the plans, and the national lobbying group the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association pledged opposition.

Heated discussions about the airport’s future continued, until the bitterly divided Hawthorne City Council decided to put the matter to the city’s voters in a November 2001 advisory ballot measure that brought the debate to a head.

Developers outspent airport proponents by more than 12 to 1 during the campaign, but on Nov. 6, 2001, more than 70 percent of the city’s voters rejected Measure A and sided with continuing to keep the airport.

With that decision made, the city decided to stop wringing its hands over the airport and to start investing in renovating the aging facility. Plans were made to add new hangars, an executive terminal, more restaurants and industrial space.

The airport shut down for 28 days to refurbish its runway completely in October 2007. New offsite developments such as the neighboring Century Business Center were built. A fledgling startup firm known as Space Exploration Inc. – better known Elon Musk’s SpaceX – as well as the design offices for Musk’s Tesla Motors auto firm were among the new companies that moved into the development.

Motorists drive by SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, Calif. File photo. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

By 2010, the transformation had become complete. Private jets were allowed to use the airport thanks to the refurbished runway. Top executives such as Musk and famed investor T. Boone Pickens began to fly their corporate jets out of Hawthorne Municipal Airport.

In May 2013, Eureka! restaurant brought gourmet dining to the airport, replacing Nat’s Airport Cafe.

The grand opening VIP party for Eureka! Tasting Kitchen at Hawthorne Municipal Airport on Tuesday, May 14, 2013. (Daily Breeze staff file photo)

“The airport has always been a jewel in Hawthorne, we’ve always loved it. Even in this economy, it’s thriving. We’re trying to pump fresh blood into it,” said airport manager Arnie Shadbehr at the time.

In December 2015, the first new commercial hangars to be built at the airport in 50 years opened, and the airport seems primed for a bright future, even as general airports in Torrance and Santa Monica are discouraging new aviation business development because they come with increased noise and pollution concerns for the closely packed in nearby residents.

Hawthorne Municipal Airport, looking north with the Century Freeway at upper right. 2001 file photo. (Brad Graverson / Staff Photographer)

Air traffic controllers Tom Morris, left, and Derk Kuyper monitor activity at the Hawthorne Airport in this March 2013 photo. (Brad Graverson / Staff Photographer)

Excerpt from an article on the B-2 Spirit Stealth Bomberfull. Full article HERE

Frail and dying at the age of 85, John Knudsen Northrop was hardly more than a brown suit full of bones as he shambled into a defense plant conference room on a January day in 1981. The occasion was both sentimental and deeply classified: The Air Force had agreed to make Jack Northrop privy to one of the nation's most secret military ventures, a revolutionary bomber soon to be code-named "Project Senior C.J."

The old man signed a secrecy oath and sat down at a table, bracketed by a half dozen executives of the company bearing his name -- Northrop Corp. An Air Force colonel ticked off the proposed bomber's vital statistics: range, speed, payload and, most important, its stealthy ability to elude radar. If successful, the bomber could turn the $250 billion Soviet air defense system into junk, a comforting prospect, given renewed tension between the superpowers.

Northrop listened intently, knotting his hands together to control their trembling. Someone hoisted a large wooden box from the floor onto the table. Opening the lid, Northrop saw an 18-inch model shaped like a boomerang, with no tail and only the faintest hint of a fuselage. It bore an uncanny resemblance to the YB-49, a "flying wing" bomber that Jack Northrop had designed and built in the late 1940s only to have the Air Force declare the plane unstable, withdraw its support and order all existing YB-49s chopped into scrap. Heartbroken, Jack Northrop had resigned from his company in 1952, an aerospace genius reduced to self-imposed exile from the industry he had helped create.

Northrop's eyes reddened and flooded with tears as he stared at this reincarnation of his flying wing. Choking back a sob, he whispered, "Now I know why God has kept me alive for the last 25 years." A month later, on Feb. 18, 1981, Jack Northrop died.

That 18-inch model has become a full-sized bomber with a wingspan of 172 feet. Project Senior C.J. has become the B-2 stealth bomber, by far the most expensive airplane ever readied for production, at more than half a billion dollars per copy.

Photo from Wikipedia